Written for RAF News May 2019

A lone prisoner aboard a spaceship takes care of a baby girl as his ship sets course for a black hole in this beautifully bleak but challenging film.

Director Claire Denis has stressed that this is not science-fiction despite the setting. This is true in as much as it is focussed on the human story over special effects, but it is far from ordinary.

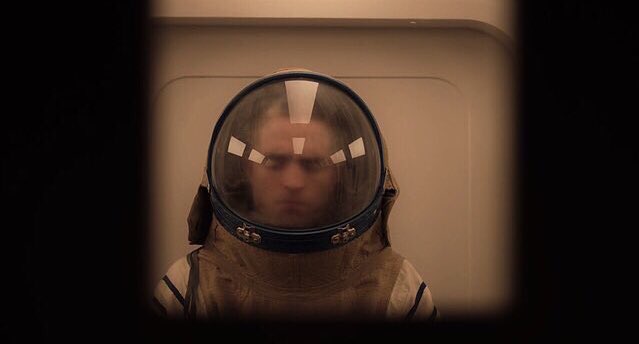

The opening features Monte (a tenderly detached Robert Pattinson) carrying out work on a rundown ship and tending to baby Willow (Scarlett Lindsey), sometimes at the same time. In this large vessel that has the isolation of Silent Running and the dirty futurism of Alien: they are alone. Single-fatherhood distilled to the elation of witnessing first steps to pleading for quiet in order to keep sane.

The initial meandering pace of High Life sets expectations for a slow meditation on the human condition, when in fact it will explore this territory but by means of a darkly tense prison drama that tips occasionally into horror and eroticism. Cutting back in time we learn about the purpose of this ship and what happened to the crew before catching up with Monte and Willow much later.

This was a penal colony for death-row inmates who had volunteered for a suicide mission to harness the power of black-holes for Earth. Along the way however they get tangled into twisted experiments of reproduction. This additional research is all under the command and control of Dr. Dibs (Juliette Binoche) who brags of being the only criminal onboard worthy of the name. Combining scientific garb with a waist-long braid she is positively witchy, keeping the others sedated and giving them drugs in exchange for their participation.

A noteworthy scene sees Dr. Dibs strapping herself into the ‘fuckbox’, an isolated cubicle that appears to simulate and stimulate simultaneously, bringing out erotic visions and sensations. Shown within a vacuum, this bizarre sensuous experience is powerful and enveloping.

The film seldom leaves the confines of the ship, and when it does it’s to mysteriously vague memories washed out with 16mm grain, creating more questions than answers, which can frustrate or delight.

Awash with mystery and symbolism High Life climbs inside your head and challenges you to make sense of it, and I accept the challenge gladly.